by Mark Allen

by Mark Allen

Every fish collecting trip has its defining highlight moment and sometimes if you are really lucky there will be more than one. I won’t soon forget collecting the long unsighted Misool Rainbowfish Melanotaenia misoolensis after an arduous two hour trek overland through scorching tropical heat during the Bird’s Head Peninsula survey back in 1999. Nor has the memory faded of spotting a loose school of dainty little Mitchell Gudgeons Kimberleyeleotris hutchinsi under a small waterfall and then dip netting some incredibly photogenic specimens while snorkelling in the gorgeous Mitchell River in northern WA back in 1998. Likewise, the undisputed highlight of a recent collecting trip to the Fly River system of Papua New Guinea was an encounter with the beautiful little Glass Blue-eye Kiunga ballochi.

Mark and Philip seining a potentially good spot for fish. G. R. Allen

Barry Crockford wrote a brief article about the species for Fishes of Sahul back in 1997 and an excellent photograph by Neil Armstrong of the fish graced the cover of that volume. In the article Barry described how he brought the first aquarium stock from PNG to Australia following the initial discovery and collections which were made by my father (Dr. Gerald R. Allen) back in 1982 (Crockford, 1997). The article ended with the unfortunate news that the entire stock, bar for one fish given to Neil (N. Armstrong, pers. comm.), was lost in the horrific Ash-Wednesday bushfires of 1983 which destroyed Barry’s fish room as well as his home. So ended the brief appearance of the species in the aquarium hobby. Aside from Barry’s article, the original scientific description (Allen, 1983), and an account of a collecting trip to the Kiunga region by Heiko Bleher in his magazine Aqua geõgraphia (Bleher, 1994), little else has been published about the fish.

In the weeks leading up to the Fly River trip in August 2007, Dad related to me a story involving Heiko. It turned out that during another collecting trip to the Kiunga region in 2003, Heiko had been unsuccessful in finding Kiunga ballochi despite rigorous sampling effort at the locality from where Dad had originally collected them in profuse numbers back in 1982. This being his fourth successive trip in search of the species, Heiko, understandably, reached the conclusion that the fish must be extinct in the wild. As a footnote to this tale, in the course of the fruitless, decade-long quest for “ballochi”, Heiko actually made the significant discovery of a second species of Kiunga (K. bleheri). Fascinated and eager to learn more, I consulted the original description of Kiunga bleheri (Allen, 2004) and the rear cover of the journal featured a photo of Kiunga ballochi. The caption below it stated: “… a beautiful species now extinct in nature”

These words extracted from Heiko’s caption were to me a palpable revelation of the frustration he must have felt having seen his dream of collecting the species in the wild go unfulfilled despite pouring so much effort into the task, and they stuck in my mind.

The rest of the team, left to right: Philip Atio, Gerald Allen and Andrew Storey. Photo by M. Allen

After spending a week collecting fish in the lower and middle Fly basin, I was beginning to gain an appreciation of just how massive the 23rd largest river system on our planet really is. The amount of water we encountered was staggering, and this was supposed to be the ‘dry’ season. Unseasonal and persistent rainfall throughout the catchment caused water levels to rise steadily and accounted for unbelievable flow velocities in the main river channel. In some floodplain areas one could have been forgiven for thinking they’d found some sort of secret tributary leading out to sea, such was the vastness of the surface area of water. It was heartening to see so much freshwater but at the same time I couldn’t help feeling a tinge of regret for the predicament we face back home in Australia which is suffering some of the worst drought conditions on record as I write this.

As any fish collector knows, lots of water and flood conditions equate to hard yakka when it comes to finding and collecting fish. I thought we did exceptionally well to emerge from the lower and middle Fly basin with over 40 different species collected and photographed under our belt. It was on Day 7 of the trip though, after the second consecutive day of failing to find anything different on the floodplain, when the decision was made to head back to the township of Kiunga where we could get out on the roads and sample some clear water shallow stream habitats of the upper Fly.

First up, we enjoyed a productive morning sampling streams along the Konkonda Road outside of town, culminating in the exciting capture of the second Kiunga species (K. bleheri) at the same creek where Heiko first discovered the fish in 1991. It wasn’t easy to catch, nor did we find very many, owing to the flooded, fast flowing and turbid conditions, but it was an encouraging find. We also snared some lovely Melanotaenia sexlineata and a juvenile Glossamia trifasciata among other species.

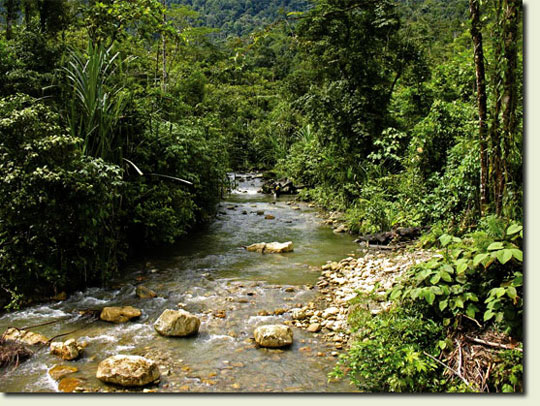

Headwater streams of the Fly were fast flowing and turbid. Photo by M. Allen

Buoyed by this collection, Dad decided it would be prudent to check for ourselves if Kiunga ballochi was indeed “extinct in nature”. While I certainly held out hope that we might find it, my confidence was dented after hearing how our field companions: Dr. Andrew Storey (formerly of the Ok Tedi Mining Ltd Environmental Department and now adjunct lecturer at the University of Western Australia) and Philip Atio (currently with OTML’s environment team) had failed to locate the species on a previous biodiversity survey of the area only months earlier. Dad, on the other hand, was more upbeat. Apparently they were so abundant back in 1982 when he first discovered them that he simply couldn’t believe that things had changed that much in the ensuing 25 years. Surely the fish was not lost forever, or was it?

Transferring the delicate catch into a breathing bag. Photo by G. R. Allen

Extinction certainly seemed a possibility at the conclusion of the next day’s collecting when we returned to home base sans “ballochi”. We had electro-shocked and seined almost every creek that crossed the Kiunga-Tabubil Highway without any luck and were forced to be contented with some brilliantly coloured Melanotaenia goldiei, Pseudomugil novaeguineae, Mogurnda cingulata and a behemoth of a Melanotaenia splendida rubrostriata (~16 cm total length).

Melanotaenia goldiei. Photo by M. Allen

Pseudomugil novaeguineae. Photo by M. Allen

Porochilus obbesi. Photo by M. Allen

We concluded that part of the reason for our failure to find “ballochi” was that we didn’t know the precise co-ordinates of the original type locality. Stupidly, I had forgotten to bring a copy of the original description containing this vital clue from home, so I emailed my wife Lina back in Perth asking her to find the paper in Dad’s reprint library (no mean feat in itself) and transcribe any information to help us locate the fish.

Lina replied the following evening summarising all the vital information contained in the paper (see Allen, 1983) including location and habitat descriptions, and lats and longs of two collecting localities. As if to mock our search effort of two days prior, this line appeared in Dad’s original remarks: “… found in large aggregations and easily netted.” This new information renewed our confidence, but Dad reminded me that he had estimated the lats and longs from a topographical map published before the road had even been built. They were only a best guess based on available resources at the time. Remember the good old days prior to GPS?

The next day we set out along the road north of Kiunga in search of our quarry yet again, but this time armed with the approximate type locality co-ordinates which were waypointed into Andrew’s GPS. I inwardly battled to suppress my expectations despite our assistant Philip’s unbridled optimism for the endeavour. At the outset of the mission he announced, “today we will find the Kiunga ballochi, I am sure of it.” …

Just under an hour later the vehicle was slowed to a crawl as we zeroed in on the first waypoint as close as the road would allow. To our collective astonishment, there was a creek right at this spot. Was this the place where Dad had collected the holotype 25 years ago? Certainly things had changed in this part of the world since 1982. Dad told us that back then the mine hadn’t yet begun operation, people were scarce, the rainforest was largely untouched and fish, of course, were abundant. Now it was almost exactly the opposite: the mine was in full swing, human population was booming, and signs of human disturbance (e.g. forest clearings, food gardens, planted sago palms) were everywhere. Most streams crossing the road were severely impacted.

This creek that we now found ourselves staring at through the grove of huge sago palms certainly was. Unperturbed, Philip and I ran the seine net through a pool in the choked and flooded creek but the place yielded no Kiunga.

Soon a group of men from the village just down the road gathered around to see what was going on. Philip told them what we were doing and about the search for the elusive “ballochi”. It was good theatre, and it piqued the local men’s interest. You could sense an air of pride amongst them when they discovered that their local creek could be the home of such an important fish.

Philip asked the men on my behalf whether there were any, less spoilt sections of the creek readily accessible by foot nearby. They nodded and we followed them into the village to the local bathing and washing area. While it was certainly in better nick than the road crossing, it was by no means pristine. Nonetheless, we dragged the net through the deeper pool sections and flooded grassy banks. Again no luck, although we managed to net some stunning Melanotaenia sexlineata with an iridescent turquoise and golden sheen as well as the first Porochilus obbesi of the trip. Not bad, but not “ballochi” either.

A dazzling king-size Melanotaenia sexlineata. Photo by M. Allen

Blue-spotted Gudgeon Mogurnda cingulata. Photo by M. Allen

The other waypoint was also a dud. There was no sign of any major creek nearby, only a tiny rivulet running through a sago grove. Things were looking grim and an air of defeat hung thick in the car. “Restricted to several small creeks located approximately 30–50 km north of Kiunga …”, read the notes from Dad’s original description. That’s a fair chunk of land, and on the way up I had counted at least a dozen creek crossings between those mile markers.

After the dismal failure at both waypoints we headed back to kilometre 30 and worked our way north, methodically collecting every creek we encountered. Frustration began setting in as creek after creek failed to produce any “ballochi”. With daylight running out, we came to one of the nicer creeks that we’d bypassed earlier because of the presence of bathing locals. Again the place was frequented by a small group of local women and children doing some laundry, but we were desperate to collect this relatively pristine looking creek so we pulled up and politely introduced ourselves, informing them of our activities which generated the typical elevated levels of amusement.

Philip and I surveyed the scene and carefully plotted a seine net strategy. The creek exited a pipe under the road into a rocky pool about chest-deep next to the culvert, then around a sharp bend, over some shallow riffles and off into impenetrable rainforest.

The water was slightly turbid and flowing rapidly. At the sharp bend a quiet backwater of flooded ferns and grasses looked a likely spot to try our luck as it was a similar kind of habitat to that in which we found the “bleheri” a few days earlier. We entered the stream and positioned the seine around the backwater, sawing the leadline along the bottom and through the vegetation before lifting it up. As we herded our catch into an ever diminishing pocket of water at the bottom of the net we looked for any trace of something small – something different.

Iriatherina werneri. Photo by M. Allen

Every time Philip or I checked under a hidden fold of net my pulse raced, but each likely candidate turned out to be a baby “rainbow”. We lifted the net completely out of the water and checked every small fish, each in turn, with hopes fading. Then just as we were about to release the catch back into the stream something small, transparent and with a hint of yellow caught the corner of my eye. Almost simultaneously Philip noticed it as well and let out a cry: “WE GOT IT!”

“We got it!” Finally a Kiunga ballochi. Photo by G. R. Allen

With my heart beating up into my throat I looked at the tiny fish almost incredulously, breathing hard from the excitement. It was about 2 cm in length, with a transparent, deepbody and vivid yellow and black markings at the fin margins. This was the fish alright, you couldn’t mistake something so distinctive or beautiful. We didn’t have anything to put the little beauty into so I hollered at Dad to fetch a bucket. Philip and I high-fived each other, and never before has my hand been slapped so hard, as we celebrated our discovery like we’d just won an AFL premiership. Dad raced back to the car, still not having seen the fish, and retrieved the bucket and a camera to record the moment for posterity. With due diligence I transferred into the bucket the first Kiunga ballochi specimen caught in the wild for over 20 years.

The little jewel we had been chasing: Glass Blue-eye Kiunga ballochi. Photo by M. Allen

Where there’s one there’s more, so Philip and I left our lone specimen in Dad’s hands for him to admire and dragged the net several more times in various parts of the creek eventually capturing four additional specimens. With daylight fast diminishing, we gave up the chase for more and transferred our prize catch into Breathing Bags before heading back to Kiunga jubilantly. The following hours were spent photographing the precious discovery.

Although it was immensely satisfying to find this fish in the wild, the difficulty involved in tracking it down certainly indicates that the species is by no means ‘out of the woods’ with regard to its conservation status. While it is not extinct in the wild, it is now known to occur for certain in only one creek within its original restricted range in the upper Fly River catchment. This area is undergoing extensive human population growth as general living conditions improve, which is a knock-on effect of the wealth being pumped into local communities by the Ok Tedi mining operation. More people means more environmental impact and of course it’s the freshwater resources that are in most demand for drinking, washing and the growing of staple crops such as sago. Adding further threat, there are now several species of non-native fishes that have gained a foothold here, the most worrying of which is the Snakehead Channa striata.

Channa striata, juvenile (left), adult (right) Photo by M. Allen

Heiko’s Blue-eye Kiunga bleheri. Photo by M. Allen

Seining for more Kiunga and the happy author in front of the K. ballochi locality. Photos by G. R. Allen

The scenic Kiunga-Tabubil highway and one of the many villages along the highway. Photos by M. Allen

This fish is as tough as ‘old boots’ and is a voracious predator of native fishes. It was commonly captured during the current survey throughout the Fly. In the past quarter of a century Kiunga ballochi has declined from being abundant to the point where it is now rare within its restricted distribution, although a truly accurate assessment of the conservation status remains practically impossible because of the lack of access to aquatic habitats throughout the range beyond the major road crossings. Who knows, perhaps aggregations the likes of which were mentioned in the original description are still common in sections of stream hidden beneath the impenetrably thick rainforest away from the highway. I certainly hope that is the case, but for now, I am more than happy just to have found this fish in the wild and I feel extremely privileged to have had the opportunity to share in the rediscovery of a true jewel of the Australia-New Guinea fish fauna.

A magic sunset over the massive Fly River, 23rd largest river on our planet. Photo by M. Allen

Postscript: Despite the elements being well and truly stacked against us we still managed to collect and photograph 65 different freshwater fish species in the Fly; by any accounts a tremendously successful trip. ANGFA members and Fishes of Sahul subscribers should keep an eye out for the new book entitled Freshwater Fishes of the Fly River (by G. R. Allen, A. Storey, and M. Yarrao) which will feature photographs taken during the expedition. It’s due out in early 2008.

References

Allen, G. R. 1983. Kiunga ballochi, a new genus and species of rainbowfish (Melanotaeniidae) from Papua New Guinea. Tropical Fish Hobby v. 32 (no. 2): 72–77.

Allen, G. R. 2004. Kiunga bleheri, a new Blue-Eye (Pisces: Pseudomugilidae) from fresh waters of Papua New Guinea, aqua, Journal of Ichthyology and Aquatic Biology 8 (2): 79–85.

Bleher, H. 1994. Kiunga. Aqua Geõgraphia. Vol. 9: 34-57.

Crockford, B. 1997. Kiunga ballochi. Fishes of Sahul 11 (2): 505–507.

This post is also available in: Italian German French Spanish Português